Getty Images

How Employers Can Achieve a Fair Price in Hospital Negotiations

With healthcare costs skyrocketing, it is time for employers to take the reins on negotiating hospital prices to achieve a fair price.

Across the nation, Americans are feeling the pressure of escalating prices in nearly every area of life, from the grocery store to the clothing store to the gas pump. The hospital room is no exception.

Hospital costs represent a significant portion of healthcare spending. Nearly a fifth of the average American’s premium dollar goes toward inpatient hospital services.

Moreover, these costs are escalating. Between 2021 and 2022, medical prices overall grew by five percent. Hospital prices, specifically, increased by 3.4 percent, outpacing growth in the prices of physician services and prescription drugs.

Employers have a particularly personal perspective on the true costs of these healthcare price hikes.

Employer-sponsored health plans saw healthcare spending spike by 6.3 percent in 2021, breaking every annual increase record in the previous ten years. While employers attributed much of this spike to increased care utilization as coronavirus pandemic restrictions lessened, they expected costs to continue to rise.

Hospital prices are at the heart of employers’ healthcare spending woes. Most employers consider hospital costs unreasonable.

Reliable data sets from organizations like the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions (National Alliance) appear to support employers’ claims that hospital prices are out of control. National Alliance’s playbook—"Beyond Hospital Transparency: Getting to Fair Price”—indicated that employers often pay 140 percent to 200 percent of Medicare prices for hospital services.

Mike Thompson, president and chief executive officer of National Alliance, urged employers to use the data compiled in the National Alliance playbook in order to secure a fairer price.

“MedPAC has indicated that a reasonably efficient hospital should be able to operate overall pretty close to Medicare. With that, you'd say, ‘well, why are plan sponsors being charged up to five times Medicare, then?’ And of course, no one knew the answer to that. Now I think we do: we're just getting price gouged, effectively, in the pricing because they can,” said Thompson. “Plan sponsors as plan fiduciaries have to take action. They can't just stand for it.”

Thompson and Karen van Caulil, president and chief executive officer of Florida Alliance for Healthcare Value, a member of National Alliance, shared strategies that self-funded employers can implement to achieve lower prices in hospital negotiations.

Assessing the self-funded employer’s responsibility

The first step in employers’ efforts to reduce hospital costs is to accept their responsibility for covering those costs.

The traditional employer-payer dynamic for a self-funded employer seems to place most of the cost burden on payers: health plans negotiate the lowest price possible for employers and take on some of the fiduciary responsibility for the employees. But this perception of the health plan’s role is inflated, van Caulil said.

“Many employers think of that health plan/third-party administrator (TPA) as holding some fiduciary responsibility for the price paid. But we have said to them: unless it's explicit in your contracts—and it typically is not—at the end of the day, the buck stops with you,” van Caulil stated.

According to National Alliance’s playbook, a fiduciary is anyone who has discretion over the health plan’s assets and is the claims administrator. This includes chief executive officers, human resources executives, chief financial officers, chief operating officers, board members, and others.

Regardless of the role, the fiduciary responsibility—as outlined by ERISA—almost always lies with the plan sponsor which, in an employer-sponsored health plan, is the employer. The extent to which an employer is a fiduciary depends on the structure of the health plan.

Those who fail to align with ERISA can face a 20 percent penalty determined by the Department of Labor and criminal penalties and may be removed from fiduciary status, the playbook warned.

“Health plans have done quite well in this environment. It isn't that they've been hurt. As long as they have competitive prices with their competitors, they pass it through to employees, to individuals, to employers. I think this is a wakeup call that, that's not good enough,” said Thompson.

“We have the data to suggest that they have not been the stewards that we thought they were being for our plans. And we know we may need to work with them to help reverse this train. We know employers have to do their part. But the employers can't do it alone. They need their TPAs and intermediaries to be on their team—not worrying all the time about their shareholders but worrying about their customers and being their advocates to get to a fair price.”

As fiduciaries, the National Alliance’s playbook and other emerging resources have made it more possible for employers to access pricing data to make an informed decision about their plan management. But that also leaves employers more liable to civil or class action lawsuits.

As a result, employers must be informed and take responsibility for their negotiations with hospitals, van Caulil and Thompson emphasized.

“Empowering the self-funded employers and educating them about the extent of their fiduciary responsibility has been critical in this,” van Caulil said.

Defining a fair price

Employers who have accepted their responsibility for securing fair prices face a massive undertaking in the very first step toward that goal. The first step is to answer the question: what is a fair price?

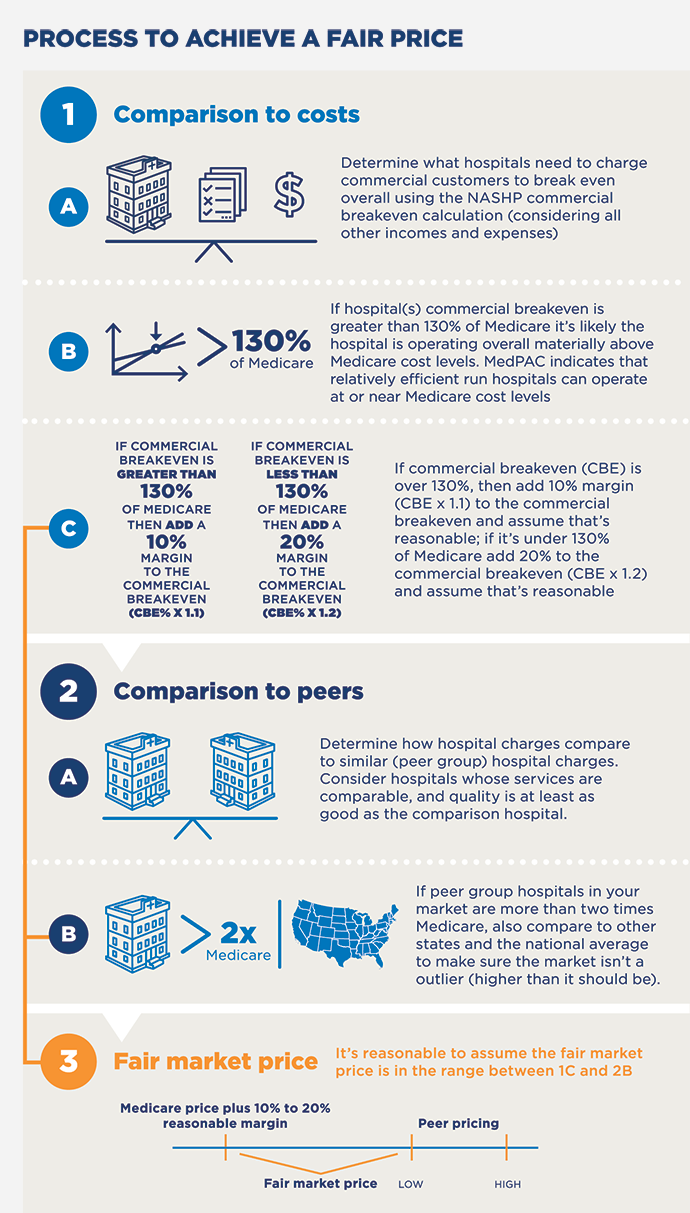

Numerous factors are at play in establishing a fair price, including geography, marketplace players, and other elements that are outside of employers’ control. Despite these variabilities, National Alliance has identified an overarching three-step process that employers can use to set a fair price as well as more specific, existing strategies for securing fair prices.

First, employers should compare costs to what hospitals need to break even. This cost can be ascertained using the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) commercial breakeven calculation.

Employers can use a reference-based approach, comparing one hospital’s prices to a specific benchmark. The Medicare price for services is the benchmark that National Alliance recommended.

An employer can assume that a hospital is not operating efficiently and cost-effectively if the breakeven point is greater than 130 percent of the Medicare price. If the commercial breakeven exceeds 130 percent of the Medicare price, National Alliance suggested adding 10 percent to the price. If it is less than 130 percent of the Medicare price, then employers should consider adding 20 percent to the margin.

Additionally, employers can contrast a single hospital’s prices to the local peer hospitals’ prices.

In this case, an employer would look at how the hospital compares to other hospitals with similar services and quality of care. In some scenarios, a market of hospitals may be an outlier with exceptionally high costs across the area. One indicator of an outlier market is that the hospital costs are twice as high as the Medicare price or more, in which case employers should compare the costs to national and other state averages.

The fair price range will fall between the reference-based price and the peer-based price.

Employers can also pursue policy-based approaches to hospital pricing by regulating across all facilities or may be enforced if prices cross a certain threshold. However, this approach will be subject to the tides of politics.

Whatever approach employers take, van Caulil stressed the benefits of using the Medicare commercial break-even number as a starting point for negotiation.

Discussing fair price, pricing data with hospitals

Employers have experienced the crippling effects of high healthcare spending for decades. Many are bracing themselves for even bigger increases in the coming years. Seven out of ten employers report that they expect healthcare spending to rise moderately or significantly in the next three years.

Hospital prices can tamp down employees’ wages and hold businesses back from growth. In a RAND study that examined the effects of hospital mergers on hospital prices and employee wages, hospital mergers increased hospital prices and contributed to a $638 drop in wages. The impact of hospital prices on wage increases is even more significant in an economy that is experiencing record-high inflation rates.

Hospitals may not take employee wage increases and local businesses into account when setting prices, so employers must communicate these factors effectively in their negotiations.

Tools like the National Alliance “Beyond Hospital Transparency” playbook, the NASHP Hospital Cost Tool, the SAGE Transparency Hospital Value dashboard, and the RAND 4.0 metrics help employers articulate the impacts that they have witnessed.

“Plan sponsors have to be more visible, and hospitals have to be more aware of the consequences of their actions,” Thompson said. “They think the health plans are paying these bills, but it's coming out of the salaries and out of the public services of school districts and teachers and real-life workers.”

In the past, one of the major points of debate between hospitals and payers, including employers, has been the validity of payers’ data on hospital spending. However, van Caulil said that this contention should be less of an issue with the tools that employers now have at their disposal.

The latest version of the 2022 NASHP hospital cost tool draws on 10 years of hospital cost data that the hospitals reported to the federal government, van Caulil shared. The 2022 RAND Hospital Price Transparency study uses employers’ paid claims. If hospitals push back on how employers assess quality of care as a factor in pricing, employers can say that the data in the RAND report comes from CMS.

“We have never had more credible data than we have right now. It’s not coming from one source. MedPAC, RAND, Rice University, NASHP—these are highly technical organizations that don't have skin in the game. We've got skin in the game as purchasers,” said Thompson.

As a result of refining these tools and establishing their reliability, van Caulil said that employers have seen far less pushback from hospitals than in previous years.

“Most of the hospitals want to figure this out with the big key employers in their markets. They see that employers now have this data and this information and hopefully are not going to back down. They can't, financially. It's reached the tipping point,” van Caulil explained.

“So, I'm encouraged. We've got a lot of meetings with hospitals set up with our employers.”

Leveraging coalitions, consultancies

While any employer can access and leverage the tools that Thompson and van Caulil identified, any effort to achieve a fair price in hospital negotiations is less likely to be successful as a solo mission.

Coalitions and benefit consultancies are key to enacting broader, lasting, and more meaningful change.

“It almost goes without saying: clearly, no one employer has the market power to influence the hospital's general pricing, but collectively they do. Coalitions become core to the ability to bring employers together and speak with a common voice,” Thompson said.

Coalitions rally multiple employers around similar goals. Specifically, region-based coalitions can be pivotal in coordinating efforts within a region or market.

For example, as of April 2022, the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchasers represented nearly 50 regional coalitions in the public and private sector, both nonprofits and Taft-Hartley purchasers. This population included the Florida Alliance for Healthcare Value as well as organizations like the Purchaser Business Group on Health, Health Services Coalition, and EdHEALTH.

“Regional purchaser coalitions with the active support and engagement of their members can play a major role in driving and leveraging transparency data to improve quality and value,” Thompson shared in the introduction to the National Alliance playbook.

“In fact, much of the transparency on quality and price achieved to date is directly attributable to the work of regional coalitions operating in the interest of employer-members.”

Employers can also lean on insights from non-coalition members like benefit consultancies as they calculate and pursue fair prices in hospital negotiations. Benefit consultants are licensed health insurance professionals who advise employers on administering their healthcare benefits, design benefit packages, and more. Benefit consultants do not work for an insurer.

Smaller consultancies can be particularly skilled at driving innovative solutions to employers’ healthcare benefits needs, van Caulil noted.

However, big health plans and small consultancies alike are discovering tools like the SAGE Transparency Hospital Value dashboard for the first time. To van Caulil and Thompson, this underscores the fact that employers must take more responsibility for negotiations.

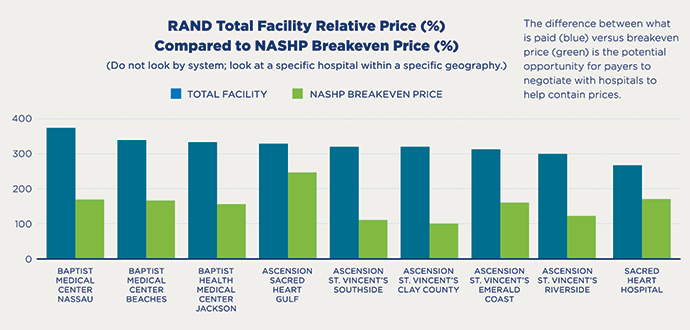

Given the weight of fiduciary responsibility and the seemingly fixed dominance hospitals have in negotiations, employers might be tempted to cave in to towering hospital prices. But self-funded employers must be aware that there is ample room for negotiation on pricing, especially in certain regions of the US.

For example, Florida ranks fourth among the top five states in the US with the highest healthcare spending overall. The state has an even worse record with hospital pricing, specifically. Florida boasts the third-highest prices in the US for hospital services alongside West Virginia and South Carolina.

Employers in Florida have been paying, on average, more than three times the cost of Medicare’s hospital price. The commercial break-even point is 148 percent, but employers may pay 345 percent for hospital services. That is a 197 percentage-point gap within which employers can negotiate a much better price.

There is room for negotiation, but only if employers take the reins. Identifying fair price goals and strategies for bringing down employers’ hospital prices are important steps, but they will not be possible unless employers understand and take ownership of their responsibility for securing fair prices—legally, contractually, and in the eyes of their employees.

“At the end of the day, employers cannot rely on their intermediaries to be their advocates,” Thompson stressed. “They need to be their advocates. And that means engaging with hospitals, engaging with their health plans, and having the health plans’ backs as they go to bat for them. If we don't take this data and make it work for us, it'll be used against us.”

Employers are undergoing an evolution as they take on a more active role in hospital negotiations. Thompson and van Caulil expressed both urgency and hope about that progression.

“This is a change process and with any change you go through those various phases—denial, anger, acceptance,” Thompson continued. “We are in the denial and anger reality with alternate sets of facts. We have to get beyond anger and denial to working together to higher value.”

“We have a continuum,” van Caulil agreed. “Education leads to awareness and then awareness leads to intent. But you've got to get employers from intent to action. Depending on whom we're working with, we’re anywhere between education, awareness, and intent. And now some of them are really moving into action.”