Getty Images/iStockphoto

4 Strategies to Advance Value-Based Care During and After a Crisis

Four experts in value-based care share how a major disruption to the healthcare industry, like the COVID-19 pandemic, could be used to advance payer value-based care progress.

How do major disruptions affect the US healthcare system’s progress toward value-based care?

A recession, a widespread natural disaster, a public health emergency—significant national events like these have the power to build or break any healthcare system, but the American healthcare system, some have argued, is particularly vulnerable.

Healthcare spending contributed over 17 percent of the country’s gross domestic product in 2018, allowing shifts in healthcare spending to affect the economy at large. Recent events also painfully tested the belief that healthcare jobs are “recession proof,” as hospitals laid off 2.3 million workers in March and April 2020 due to the pandemic.

The extremes and unknowns of a major disruption may impose chaos on the healthcare industry. However, disruptions like the coronavirus pandemic can also push the industry toward value-based care.

Across the industry, 43 percent of healthcare leaders agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the coronavirus pandemic would propel the industry away from fee-for-service, according to a recent Insights report from Xtelligent Healthcare Media. Among those, nearly half of all payer respondents agreed or strongly agreed.

“Payers certainly have their pressures, but this is a real opportunity for them to think about how to take advantage of this silver lining and really move forward with the value-based new normal,” said Mark Fendrick, MD, Director of the Center for Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan.

Pursuing global payments, forming sustainable, long-term value-based care contracts, better integrating social factors, and re-evaluating healthcare spending are four key steps to maintaining value-based care progress during a major disruption, Fendrick and payer experts indicated.

Establish value-based reimbursement models, global payments

Major healthcare disruptions can allow payers to rethink their current payment models and angle themselves more towards alternative payment models that will support providers through the disruption. Global payments can be a strong payment model in times of upheaval in the industry.

Global payments (also called “global capitation” or “global budget”) are a form of level, or “capitated,” payment by which a payer sends a provider fixed, periodic payments to cover all of a patient’s care for the specified time period. Payments are frequently made on a per member per month model and may cover diagnostics, home health, inpatient and outpatient services.

Common features of a global payment model include:

• Financial structures built around a baseline budget

• Administration and oversight of cost and performance

• Stakeholder engagement that is aligned, communicative, and may pull from across the healthcare industry, including federal representatives

John Bennett, MD, president and chief executive officer of Capital District Physicians’ Health Plan (CDPHP), saw firsthand the benefits of global payment models during a major disruption to the healthcare system.

At CDPHP, around nine in ten of their primary care physicians are in a value-based care model. However, there are still providers—mostly hospitals and specialty providers—that have not joined CDPHP’s global payments model.

When the pandemic hit, CMS asked providers to stop performing elective services and, as a result, the healthcare delivery system took a major financial hit, particularly the hospitals.

Inpatient volume dropped by almost 20 percent and outpatient volume fell by nearly 35 percent, compared to hospitals’ baselines, the American Hospital Association (AHA) reported.

AHA estimated that even if providers return to their baseline volume of care delivery by the close of 2020—which over two-thirds of AHA members think is impossible—they would still lose about $116.7 billion in revenue.

These losses threatened providers who were not in value-based care agreements like CDPHP’s global payment model with partial or complete closure. But CDPHP’s providers who were in a global payment model were largely protected from these risks because they continued to receive their monthly payments even with most care delivery on pause.

“Our primary care practices that are on our value-based payment models are on a global payment, so they get a membership attributed to them and they get a risk-adjusted payment,” Bennett explained to HealthPayerIntelligence. “When they weren't able to do visits for a couple of weeks due to the coronavirus pandemic, they still got paid.”

These types of payment models, like many alternative payment models, can be unappealing to providers because of the risk involved.

“Under a global payment arrangement, the ACO bears the risk that payments received are insufficient to cover the costs of the services it provides. To assume global risk successfully, ACOs need a suite of tools and systems to monitor and manage cost and utilization that is similar to those currently used by payers,” the American Academy of Actuaries has noted.

However, a significant benefit of the global payment model is that these models can be constructed with or without risk attached.

“The level of payment can be risk adjusted and there can be quality and service metrics for bonuses,” said Bennett. “We've had that model with our primary care physicians for years and it works very well.”

But Bennett was careful to emphasize that providers should be responsible for performance risk but not insurance risk.

Performance risk versus Insurance risk: “An effective payment system should ensure that payers retain insurance risk (i.e., the risk of whether patients have health problems or more serious health problems) and that providers accept performance risk (i.e., the risk of whether care for a particular health problem is delivered efficiently and effectively),” a brief by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Network for Regional Healthcare Improvement explained. Strategies to ensure that payers take on insurance risk while providers take on performance risk include risk adjustment or risk stratification and risk corridors.

To protect CDPHP providers who were not in global payment models, the payer decided to temporarily extend its global payment model across its entire network during the public health crisis.

Thus, the coronavirus pandemic became like an experiment for providers not already engaging in this type of value-based reimbursement.

During the crisis, CDPHP sent advance payments to providers who had not yet joined the global payment models, including fee-for-service providers. CDPHP tracked claims and if they fell below a predetermined level, the payer wrote the providers a check to cover the difference.

The advance payments did not disrupt the pay cycle for providers already on the global payment model. For providers who were not, CDPHP will take the advanced payment out of future reimbursements when the providers are in a better state financially.

But Bennett expressed hope that this experience would accelerate uptake among providers not yet in the global payments model.

"It's very successful,” Bennet said of the risk-adjusted global payment model. “I’d like to use this crisis to expand the model to specialists and I'd love to do it with hospitals as well.”

Ensure that new value-based contracts have long-term sustainability

Extreme disruptions can be a value-based care conversion experience for providers.

“With the pandemic, providers recognized very quickly that if they had more lives flowing through risk agreements, maybe more intensive risk type arrangements, then they would have had revenue protection from the impacts of decreased utilization and the evaporation of fee-for-service type visits,” Jason Woods, vice president of provider network strategies at Priority Health, explained.

When this occurs and providers begin to show more interest in pursuing a value-based care contract, it may be tempting to leap into a value-based care model that serves as a quick fix for the damage a major disruption inflicts.

However, Woods urged payers to think long-term.

“The challenge has been getting providers stood up as quickly as possible in value-based arrangements, but also recognizing then that these have to be longer term arrangements,” Woods said.

Although regulations may be waived during a crisis, payers need to keep typical standards—such as HEDIS measures and CMS requirements—in mind while setting up new value-based contracts during a disruption.

For example, CMS waived quality metrics reporting for the year due to the coronavirus. Nonetheless, payers should establish their 2020 value-based contracts in a way that these partnerships will continue to thrive once those waivers end.

“While we get favorability for 2020 because of the pandemic, ultimately we're going to have to have good long-term performance,” explained Woods.

Part of ensuring strong long-term performance is ensuring that providers have access to the data that they need. This includes not just performance data, but also data regarding what the contract will require of them in the future.

“We’re making sure that we've got the right transparency around the economics and that we're making clear to them what's involved in the pricing targets. And we’re making sure that we can really help support them in making the behavioral changes that are necessary in order for those agreements to work long term,” Woods said.

Support social determinants of health factors, community-based organizations

A major disruption also may cause, underscore, or exacerbate social factors. For example, a large natural disaster or series of natural disasters could cause widespread food insecurity. A recession may result in foreclosures and housing instability.

During the coronavirus pandemic, multiple social determinants of health factors have surfaced, more broad and intense than before. For instance, broadband access for telehealth, transportation, and employment were all social determinants of health that existed before coronavirus, but the pandemic intensified barriers.

To Caraline Coats, vice president of Bold Goal and Population Health Strategy of Humana, now is the time to better integrate social determinants of health and social risk factors into value-based care processes.

The healthcare system needs to institute a standardized set of social determinants of health codes for reimbursement, Coats urged.

“Until we have standardized social risk index data to diagnose health-related social needs and a provider network that is built to include social resources, in addition to clinical, we are working in a fragmented system that does not have a sustainable financial model to support,” Coats told HealthPayerIntelligence.

She said that payers are in the position to push this kind of reform forward during the pandemic by collecting more data for a social risk index and influencing policy on reimbursement and coding.

Furthermore, payers can reinforce community-based organizations during a pandemic to drive forward value-based care.

Often, community-based organizations are on the front lines assessing and addressing social determinants of health alongside health conditions. These organizations may already face resource and funding shortages outside of crisis mode. As a result, community-based organizations experience even greater duress during a catastrophe when they are most needed.

Under such circumstances, payers can step in to support their community-based partners in ways that advance value-based care progress.

Coats suggested that these organizations would benefit from a platform that enables community-based organization referrals, similar to Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City’s referral network.

“The pandemic accelerates the need for all of this as our social health needs are more important than ever to address as part of our whole person health,” said Coats. “Payers can continue to push for more screenings, more data, advanced payment models and outcomes-based payment to support the CBOs.”

Re-evaluate healthcare spending, eliminate low-value costs

When the healthcare system experiences a major disruption, unnecessary expenditures become clearer.

Due to deferred care, the current crisis set payers atop a pile of unused premium revenues. UnitedHealthcare, for example, reported a net margin for the second quarter of 2020 that was more than double the percentage its 2019 second quarter net margin. Payers came under fire from the public and from the federal government for accruing profit while the nation suffered.

Fendrick recognized the need for some payers to be more conservative since deferred care will likely result in high healthcare spending in the future. Furthermore, payers may use telehealth to control costs, but it could also expand providers’ footprints leading to unknown spending.

Fendrick exhorted payers to use this unexpected margin of income to advance value-based care by re-evaluating their healthcare spending and cutting out the unnecessary costs.

“Payers have this really unusual opportunity to start paying for things that they always should've been paying for: evidence-based services that make individuals and populations healthier. And they can also start becoming a bit more courageous about not paying for things that don't make Americans healthier,” Fendrick asserted.

Having coined the phrase “value-based insurance design” and written more than 250 articles and book chapters on the subject, Fendrick was well-positioned to recognize the opportunities that this disruption posed for value-based care progress.

There are myriad examples, but consider cancer screenings alone.

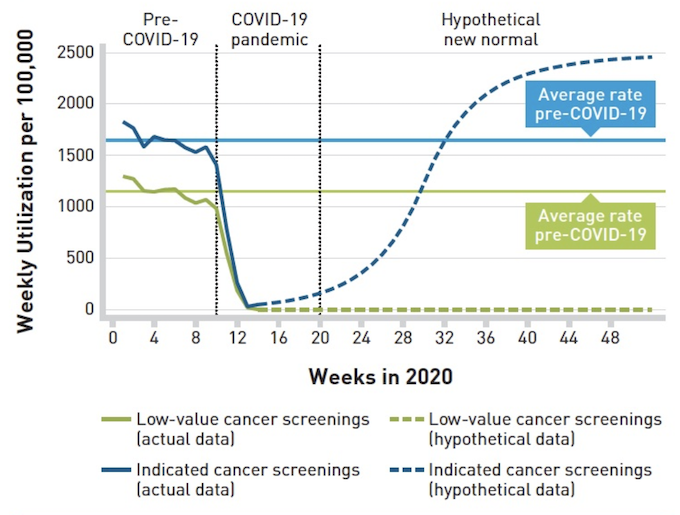

In his recent publication in the American Journal of Managed Care, Fendrick indicated that whether a cancer screening is high-quality or not depends on various patient-related factors, such as age, and also frequency and the site of care.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, low-quality cancer screenings for colorectal, prostate, and cervical cancers were still common. When the pandemic hit the US, all screenings came to a halt. Now, the healthcare industry faces a decision regarding how it will pick up screenings.

Fendrick and his co-authors recommended leveraging alternative payment models rooted in patient outcomes and electronic health record adoption, and those that tie patient cost-sharing to the quality of care they receive—so that they pay less for high-quality service.

Authors’ analysis of commercial insurance claims data the (OptumLab Warehouse Data) among Medicare Advantage enrollees. Low-value cancer screenings (green lines) include prostate cancer screening among men 70 years and older, cervical cancer screening among non-high-risk women older than 65 years, and colorectal cancer screening among adults older than 85 years. Indicated cancer screenings (blue lines) include prostate cancer screening among men younger than 70 years, cervical cancer screening among non-high-risk women 65 years and younger, and colorectal cancer screening among adults younger than 75 years. The solid lines represent the actual utilization data prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas the dotted lines represent hypothetical trends to highlight what should happen in the post-COVID-19 era.

“Set up new value-based payment arrangements and benefits designs that are aligned for physicians, clinicians, and their patients to have easily accessible and affordable services, services which the evidence shows will make them healthier,” Fendrick explained.

“Pay the clinicians adequately for doing those services. Then, hold them accountable for the things they shouldn't have been doing.”

The unanticipated pause in primary care and elective services offered an opening that could reveal unnecessary or low-quality treatments.

“We can create a model in which we're going to continue to deliver high value care regardless of the next pandemic,” Fendrick said. “We can make it happen right now because it's not like we're paying all of this money out for these low value services. This is our time.”